Did you ever eat a salad made up of only string beans and onions?

In the summer of 1970, after one season of promoting 15 fights in eight months at the Blue Horizon, I was sitting across the table from Jimmy Iselin at The Palm restaurant in New York City.

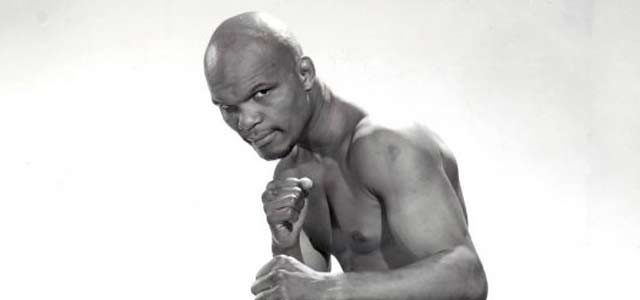

Iselin’s dad, Phil, owned the New York Jets and the son owned Bennie Briscoe’s managerial contract. Briscoe, a middleweight, had labored for eight years in the shadow of Gypsy Joe Harris and Stanley “Kitten” Hayward, never a big draw, just a tough guy no one wanted to fight.

Briscoe’s record was 32-9-2, 24 KOs. Iselin had purchased Briscoe’s contract two years earlier from Pinny Schafer, the head of the Bartenders Union in Philadelphia. Iselin sent Briscoe to train in the Catskills under Joe Fariello, leaving behind Quenzell McCall, who had taken over those chores from Yank Durham.

The 27-year-old Briscoe was bouncing between managers and trainers with no direction. Things had come to a boiling point earlier that year.

Bouie Fisher, a friend of Briscoe’s and later the trainer for Bernard Hopkins, had a brother, Willie, who didn’t like the way Briscoe was being handled. To prove this, Willie made a phone call from Philadelphia to Fariello in the Catskills before Briscoe went to training camp. Willie asked Briscoe to pick up the phone in another room and listen without letting Fariello know.

Willie asked Fariello if he planned to change tactics for Briscoe’s upcoming rematch with Joe Shaw, who had upset Briscoe late in 1969 at The Spectrum. Fariello said there wasn’t much Briscoe was capable of learning; that he (Fariello) would wind him up like a toy robot and send him out to fight.

That was, as they say, all she wrote for Fariello.

Briscoe told Iselin he was not going back to the Catskills; he was going to train for the Shaw rematch with Quenzell McCall in Philadelphia.

Iselin threatened to call off the fight. Briscoe appealed to the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission, who ruled that only a training injury could stop the fight since contracts had been filed.

With McCall in charge, Briscoe wore down Shaw after six rounds of a brutal war at the Arena. Iselin came to the fight and took his share of Briscoe’s purse. This was March 16, 1970.

Several months later, I was speaking with Jack Puggy, who had been in boxing his entire life, first as a manager and then as a matchmaker for legendary promoter Herman Taylor. Puggy said he has been asked to buy Briscoe’s contract, but did not want to spend the money, which was in the low four figures.

I had been promoting three middleweight prospects who looked like they were headed for big things—Eugene “Cyclone” Hart, Willie “The Worm” Monroe, Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts. Each of them eventually would have to fight Bennie to become No. 1 in the city and whoever had Briscoe would be the promoter of those big fights.

I asked my brother-in-law, Arnold Weiss, to buy Briscoe’s contract. He wrote a check to Iselin and handed it to me and I got on a train to New York and met Iselin at The Palm.

Iselin told me how good the string bean and onion salad was. Trying to act sophisticated—I was 23 and this was my first time at The Palm—I ordered it. We did our business and, as soon as I handed him the check, he got up and made a phone call to Fariello. They were ecstatic and so was I.

Back home and happy with McCall in his corner, Briscoe scored 11 consecutive knockouts and developed into a box-office attraction, drawing crowds to the Arena and Spectrum, bowling over tough guys like Tom “The Bomb” Carlos Marks, and Juarez DeLima, then getting off the floor twice in the first round to rally for an incredible second-round knockout over Rafael Gutierrez on the annual Deborah Hospital show late in 1971.

One year later, Briscoe was one punch away from the world middleweight title, having nailed Hall-of-Famer Carlos Monzon with a right hand in the ninth round of their title fight in Buenos Aires, Argentina. But Monzon, with the help of a slow-moving hometown referee, held on until the bell sounded, eventually winning a 15-round decision.

Briscoe rebounded, winning six of his next seven by knockout, including the one that rates as my favorite, his knockout over the highly publicized Australian Tony Mundine in Paris early in 1974.

That one landed him a rematch with Rodrigo Valdes for the WBC version of the title. Valdes had barely beaten Briscoe over 12 rounds the year before in New Caledonia in the South Pacific.

There was trouble in the Briscoe camp. McCall, who never liked my brother-in-law, brought a lawyer to the fight in Monte Carlo. When I arrived two days before the fight, the lawyer informed me that he was going to break Weiss’ contract, but that I could continue to promote Bennie. That was nice of him!

The problem was, they had Briscoe believing he wasn’t being treated fairly. Who knows what went through Briscoe’s mind but he weighed-in at a light 157 ½ pounds and was stopped for the only time in 96 fights when a desperate, bloody and nearly beaten Valdes pulled a right-left combination out of left field late in round seven. Briscoe went down, struggled to his feet, and English referee Harry Gibbs waved it off at 2.54. Valdes spent two days in the hospital.

The lawyer vanished. What a surprise! And, after Briscoe’s lackluster loss six months later to Emile Griffith at The Spectrum, McCall was replaced by George Benton, the Hall-of-Fame middleweight who was getting his feet wet as a trainer.

Unbeaten in his next 13 fights, which included a win over future light-heavyweight champion Eddie Mustafa Muhammad and a brutal draw and even-more brutal one round knockout over “Cyclone” Hart, Briscoe was back in there with Valdes, this time for the undisputed title after Monzon retired.

In a 500-seat casino ballroom in Campione, Italy, which rests on the border between Italy and Switzerland, Briscoe lost a close 15-round decision and his last shot at the rainbow. He was 34.

After losing to future champ Vito Antuofermo early in 1978 in Madison Square Garden, Briscoe flew to Kansas City where, in front of more than 10,000—larger than the crowd there in 1937 for Joe Louis vs. Matie Brown—he chopped up local hero Tony Chiaverini, winning by KO in eight rounds.

In late summer, Bennie and Marvelous Marvin Hagler drew 14,950 to The Spectrum, the largest indoor crowd for a non-title fight in Pennsylvania history. Briscoe cut Hagler early and was in the fight for four rounds, but Hagler’s stick-and-move strategy kept Bennie’s old legs off balance and Hagler won by decision.

I asked Briscoe to quit after he lost to Richie Bennett early in 1980 at the 69th Street Forum in Upper Darby. He wanted to keep fighting and we parted company. He lost four of his last seven, including his finale Dec. 15, 1982. He was approaching his 40th birthday.

His career record was 66-24-6, 53 knockouts. Pick up any boxing magazine which has a story on the best never to win a world title—back in the day when there was only one world title—and, inevitably, Briscoe’s name always makes the list.

By the way, if you ever go to The Palm, try their string bean and onion salad. They still my serve it!

(written in 2006)